Multiculturalist Ideology (Part One): A Rationale For Race War Politics

An Examination Of The Logic of Multiculturalism

An Examination Of The Logic of Multiculturalism

The recently published Home Office report (frequently referred to as a paper – presumably due to its inadequacy) into the grooming-gang rape epidemic that has swept the UK, came with a Forward from the Home Secretary herself, Priti Patel.

In that Foreword, Priti Patel wrote (Italics my own emphasis):

‘An External Reference Group, consisting of independent experts on child sexual exploitation, reviewed and informed this work. While this is a Home Office paper, it owes a great deal to the experts who provided honest, robust and constructive challenge. I am grateful to them for their time and their valuable insight. The paper sets out the limited available evidence on the characteristics of offenders including how they operate, ethnicity, age, offender networks, as well as the context in which these crimes are often committed, along with implications for frontline responses and for policy development. Some studies have indicated an over-representation of Asian and Black offenders. However, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the ethnicity of offenders as existing research is limited and data collection is poor. This is disappointing because community and cultural factors are clearly relevant to understanding and tackling offending. Therefore, a commitment to improve the collection and analysis of data on group-based child sexual exploitation, including in relation to characteristics of offenders such as ethnicity and other factors, will be included in the forthcoming Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy.’

In paragraph 3, the External Reference Group (ERG) was described as being ‘made up of experts on child sexual exploitation and abuse across a range of sectors, including representatives of victims and survivors, law enforcement, academia, the third sector, and parliamentarians’. The members of the ERG are listed:

Paragraph 4 admits: ‘The ERG had an advisory role in the development of this paper, and as such all comments from the ERG were considered carefully, but not all were taken onboard. The final paper is ultimately a Home Office product and does not reflect the position of all ERG members.’ Priti Patel’s comment about how the report ‘owes a great deal to the experts’ immediately following her comment about how the ERG ‘reviewed and informed this work’ should be taken as being disingenuous.

Paragraph 5 states (italics my own emphasis): ‘Throughout their discussions, ERG members were clear that group-based CSE is an important issue that warrants significant government attention. However, they recognised that this is a complex and nuanced area. The group recognised the difficulties in defining group-based CSE, particularly as a form of abuse that is distinct from other types of CSE and child sexual abuse more generally. The group agreed that these definitional challenges contribute to a lack of robust research and data in the public domain on group-based CSE. It was also highlighted that much of the evidence available is now quite old and therefore is unlikely to represent current thinking and understanding of group-based CSE. The ERG was broadly supportive of the aims of this paper in trying to achieve a rounded picture of the nature of offending with a mix of data, research and more illustrative detail from case studies and local reviews.’ In other words, the ERG were being spoken down to and were bullied into accepting that the issue was far too complicated for the experts to actually do anything constructive, other than to talk about it and demand more research. The carefully crafted form of words in the paragraph should be noted.

Paragraph 8 states (italics my own emphasis): ‘The group expressed differing views in relation to the scope of the paper, including how tightly drawn the definition of group-based CSE should be for the purposes of this paper. Some members felt that the paper needed to position group-based CSE more clearly in the context of wider CSA, and highlighted the risk that a narrow focus on CSE by groups could contribute to failures to recognise and tackle other forms of CSA [child sexual abuse] and CSE that have received less attention.’ In other words, the ERG itself was split sufficiently to warrant mention. That split included an objection from some (or someone) as to the determination to impose a definition as to the scope of the report. The paragraph reveals that there was a determination, including by some on the ERG, to prevent the report being focused on grooming gangs.

Paragraph 9 states (italics my own emphasis): ‘The ERG also did not reach consensus around how the evidence should be presented, particularly with regard to cultural and community contexts. While this has been a central consideration both in the development of the paper and the research that informed it, the available evidence is weak and robust data is scarce. Some, but not all, members of the group wanted to see more explicit detail on manifestations of group-based CSE when perpetrated by offenders from certain communities, particularly Pakistani communities, given the involvement of Pakistani-ethnic offenders in a number of high-profile cases and the recognised need for specific responses to specific threats. In finalising the paper, we have sought to be as specific as we can be, despite the lack of available evidence on cultural drivers in particular.’

The disagreement as to the report’s purpose is reflected throughout. Paragraph 25 states: ‘This paper considers the evidence base for characteristics of group-based CSE offending in the community’ and ‘We have focused primarily on offending by adults against children, although some of the cases we examined involved offenders who were under the age of eighteen.’ Paragraph 28 states: ‘The primary aim of this paper is therefore to present as comprehensive an assessment as possible of this form of abuse, using the best available evidence. We intend for this paper to be useful to leaders and practitioners wishing to better understand the characteristics of group-based offending in order to develop targeted responses. The paper outlines the main challenges local and national agencies face in responding to group-based CSE, sets out implications for national and local responses, and highlights necessary future work in this area, including new research.’ Paragraph 37 states: ‘For the avoidance of doubt, our work has focused on child sexual exploitation perpetrated by groups, as per the above definition, which therefore includes what commentators sometimes describe as “grooming gangs”.’ Paragraph 50 states: ‘The work that has informed this paper was aimed at better understanding the characteristics of group-based child sexual exploitation offenders and offending, and this paper reflects that emphasis. Our ultimate aim is to prevent sexual exploitation, and to ensure better safeguarding and support for victims and survivors. We consider it important therefore to present these findings in the context of a broader understanding of who experiences child sexual exploitation and how it affects them.’

The report devotes four paragraphs to bemoaning the available data. Paragraph 65 states: ‘Throughout our work on group-based CSE … a consistent challenge has been the paucity of data. This lack of good quality data limits what can be known about the characteristics of offenders, victims and offending behaviour, as data is only available on the small proportion of known cases. It is therefore important that the data that is available is of high quality and shared effectively between different agencies. Several factors contribute to this.’ It should be noted that the ‘known cases’ are dismissed as being a ‘small proportion’ of a total. That is a highly subjective statement that is the opposite of the facts as to the scale of the epidemic.

Paragraph 66 states that due to ‘under-reporting’: ‘Many victims cannot or do not disclose their abuse to the authorities, and nor is it identified by safeguarding professionals, so the abuse remains uncovered.’

Paragraph 67 states: ‘In our work to improve the recording and collation of data on group-based child sexual exploitation, we have found that a lack of clarity around definitions of groups, gangs, and sexual exploitation contribute to inconsistencies in recording. There remains confusion amongst practitioners around what constitutes group-based CSE.’

Paragraph 68 states: ‘Even where CSE is identified, the data relating to CSE is still often inconsistently recorded. For example, research has found that information is often recorded inconsistently about victims and offenders, with different agencies focusing on different aspects when recording information. Police data in particular suffers from a lack of consistency in recording.’

None of this nitpicking goes to the substance of the issue.

Under the heading ‘Ethnicity’ the report presents ‘key findings’ (italics my own emphasis):

Paragraph 75 elaborates: ‘There is a limited amount of research looking at the ethnicity of perpetrators of group-based CSE, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about whether or not certain ethnicities are over-represented in this type of offending.’ And: ‘Data in this space is reliant on “known” or identified offending behaviour, therefore limiting our understanding of group-based CSE in its entirety.’ And: ‘Law enforcement data can be particularly vulnerable to bias, in terms of those cases that come to the attention of the authorities, and this can impact on the generalisability of such data. This can also lead to greater attention being paid to certain types of offenders, making that data more readily identified and recorded.’ And: ‘Police-collected data on ethnicity uses broad categories and requires the police to assign an ethnicity rather than it being self-reported by offenders. Data is therefore not always accurate … Data on ethnicity are not routinely or consistently collected by police forces and other agencies … many research and evidence collections have a lot of missing or incomplete data.’

Paragraph 81 states (italics my own emphasis): ‘While some of the research set out above suggests that there are high numbers of offenders of Asian or Black ethnicities committing group-based CSE offences, it is not possible to say whether these groups are over-represented in this type of offending. As set out in paragraph 75, research to date has relied on poor-quality data with a number of weaknesses. It remains difficult to compare the make-up of the offender population with the local demography of certain areas, in order to make fully informed assessments of whether some groups are over-represented. Based on the existing evidence, and our understanding of the flaws in the existing data, it seems most likely that the ethnicity of group-based CSE offenders is in line with CSA more generally and with the general population, with the majority of offenders being White.’

The report’s assertions and hints about the ‘local demography’, or that an alleged ‘lack of … data in the public domain’ due to ‘definitional challenges’, and that what evidence is available ‘is unlikely to represent current thinking and understanding’, are no more than dishonest sophistry. There is no evidence that ‘the majority of offenders [are] White’. The Home Office should not embark on an exercise of trying to find (ie fabricate) evidence to ‘represent current thinking and understanding’.

There is no evidence of there being a multitude of White grooming gangs. The same cannot be said of those from particular immigrant communities. The report is a brazen cover up. Of note, is the fact that the terms ‘Muslim’, ‘Islam’, the ‘Koran’, ‘immigrant’, ‘immigration’ or ‘English’ (the overwhelming majority of victims are English) are not mentioned even once in the report. The overwhelming majority of those committing these heinous crimes are Muslims, many of whom immigrated to the UK. That they are picking on white children would indicate a racial motive and/or a contempt for those regarded as infidels, and this should investigated and not ignored.

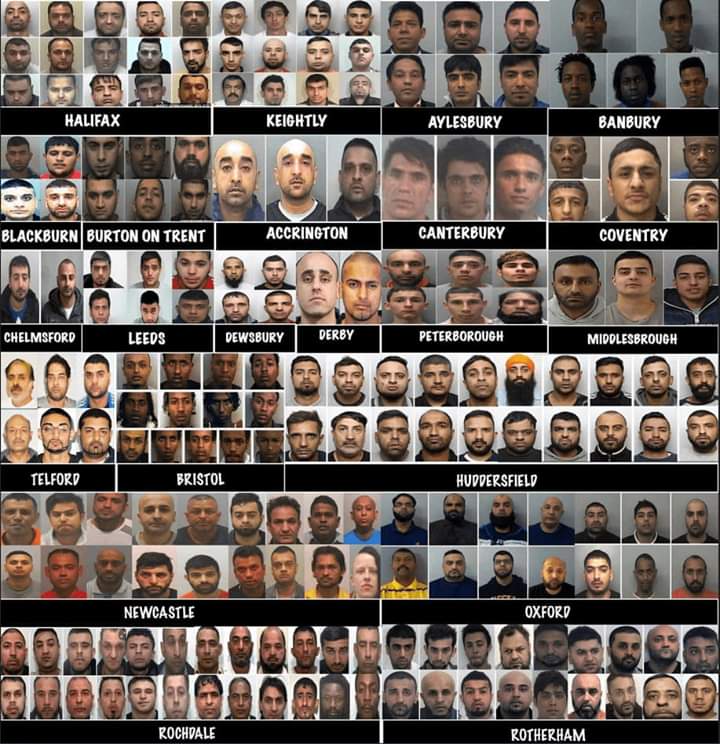

Despite the report complaining about a ‘lack of robust research and data in the public domain’, the fact is that there have already been reports and belated police investigations into the abuse, and there is evidence ‘in the public domain’. For example, there is the photograph showing the faces of many of the offenders, and there are very many other photographs. A casual look on Wikipedia is also informative.

The list of grooming gang offenders convicted in Bristol names: Liban “Leftback” Abdi, Mustapha “Greens” Farah, Arafat “Left Eye” Osman, Abdulahi “Trigger” Aden, Mustafa Deria, Said “Target” Zakaria, Mohamed “Deeq” Jumale, Jusuf “Starns” Abdirizak, Sakariah “Zac” Sheik, Abdirashid “Abs” Abdulahi, Omar Jumale, and Mohamed “Kamal” Dahir.

In Derby, those convicted were: Abid Mohammed Saddique, Mohammed Romaan Liaqat, Akshay Kumar, Faisal Mehmood, Mohammed Imran Rehman, and Graham Blackham.

In Halifax, those convicted were: Hedar Ali, Haider Ali, Khalid Zaman, Mohammed Ramzan, Haaris Ahmed, Tahir Mahmood, Taukeer Butt, Amaar Ali Ditta, Azeem Subhani, Talib Saddiq, Sikander Malik, Mohammed Ali Ahmed, Aftab Hussain, Mansoor Akhtar, Sikander Ishaq, Aesan Pervez, Furqaan Ghafar, Basharat Khaliq, Saeed Akhtar, Naveed Akhtar, Parvaze Ahmed, Izar Hussain, Zeeshan Ali, Kieran Harris, Faheem Iqbal, and Mohammed Usman.

In Newcastle, ‘the 18 gang members … convicted of nearly 100 offences’ were: Mohammed Azram, Jahangir Zaman, Nashir Uddin, Saiful Islam, Mohammed Hassan Ali, Yasser Hussain, Abdul Sabe, Habibur Rahim, Badrul Hussain, Mohibur Rahman, Abdulhamid Minoyee, Carolann Gallon, Monjour Choudhury, Prabhat Nelli, Eisa Mousavi, Taherul Alam, Nadeem Aslam, and Redwan Siddquee.

In Oxford, those convicted were: Kamar Jamil, Akhtar Dogar, Anjum Dogar, Assad Hussain, Mohammed Karrar, Bassam Karrar, Zeeshan Ahmed, Bilal Ahmed, Mustafa Ahmed, Assad Hussain, Kameer Iqbal, Khalid Hussain, Kamran Khan, Moinul Islam, Raheem Ahmed, Alladitta Yousaf, Haji Khan, Naim Khan, Mohammed Nazir, Tilal Madhi, Salik Miah, and Azad Miah.

For Peterborough, those convicted were: Hassan Abdulla, Renato Balog, Jan Kandrac, Yasir Ali, Daaim Ashraf, Mohammed Abbas, ‘Unnamed Child’, Muhammed Waqas, Zdeno Mirga, and Mohammed Khubaib.

For Rochdale, those named were: Shabir Ahmed, Mohammed Sajid, Kabeer Hassan, Abdul Aziz, Abdul Rauf, Adil Khan, Mohammed Amin, Abdul Qayyum, and Hamid Safi. Another ten, unnamed, in a second grooming gang were subsequently convicted.

Rotherham has been particularly badly affected by not only the grooming gangs, but also by the determined attempts by the authorities to cover up. Those named in various trials are: Razwan Razaq, Umar Razaq, Zafran Ramzan, Mohsin Khan, Adil Hussain, Qurban Ali, Arshid Hussain, Basharat Hussain, Bannaras Hussain, Karen MacGregor, Shelley Davies, Sageer Hussain, Basharat Hussain, Ishtiaq Khaliq, Masoued Malik, Waleed Ali, Asif Ali, Naeem Rafiq, Mohammed Whied, Basharat Dad, Nasser Dad, Tayab Dad, Mohammed Sadiq, Matloob Hussain, Amjad Ali, Zalgai Ahmadi, Sajid Ali, Zaheer Iqbal, Riaz Makhmood, Asghar Bostan, Tony Chapman, Khurram Javed, Mohammed Imran Ali Akhtar, Nabeel Kurshid, Iqlak Yousaf, Tanweer Ali, Salah Ahmed El-Hakam, Asif Ali, Aftab Hussain, Abid Saddiq, Masaued Malik, Sharaz Hussain, Mohammed Ashen, and Waseem Khaliq.

Of the Jay report into the horror of what happened in Rotherham and the attempts, including violent attempts, to intimidate witnesses, victims and those raising the alarm, it is stated on Wikipedia:

‘The police had shown a lack of respect for the victims in the early 2000s, according to the report, deeming them “undesirables” unworthy of police protection. The concerns of Jayne Senior, the former youth worker, were met with “indifference and scorn”. Because most of the perpetrators were of Pakistani heritage, several council staff described themselves as being nervous about identifying the ethnic origins of perpetrators for fear of being thought racist; others, the report noted, “remembered clear direction from their managers” not to make such identification. The report noted the experience of Adele Weir, the Home Office researcher, who attempted to raise concerns about the abuse with senior police officers in 2002; she was told not to do so again, and was subsequently sidelined.’

Little has changed in the Home Office.

It is blindingly obvious that the overwhelming majority of those named are from the immigrant communities and are Muslims. The allegation in the Home Office report of ‘the majority of offenders being White’ is a barefaced lie to distract attention from the real culprits. The report is a cover up.

The grooming, rape and gang rape of mostly English children continues.

Priti Patel should resign.